The Superbars

In our previous vignette on Latino gay bars, we discussed how the search bar feature on Mapping the Gay Guides allows users to look more closely at the data, beyond just the helpful dropdown filters. Think of this as installment number two of the Search Bar Series, this time exploring the concept of “superbars.” Beginning in 1975, the Damron Address Books included some description information referring to so-called “super bars.” That year, Damron noted Miami’s Le Club Menage was the “newest super bar” while Atlanta was about to see “yet another ‘super bar’ scheduled to open in near future.”

But exactly were these so called “superbars?” To put it simply, superbars were massive bars and clubs that formed a nightlife complex. Those Americans, especially those in major urban centers, looking for a fun night out on the town often hoped to dance at large nightclubs. Superbars often contained multiple rooms and dance floors, with state-of-the-art sound systems, and a variety of bars. They were originally intended to appeal to a wide demographic of patrons. While a dive bar with no dance floor might bore some gay men looking to boogie, disco clubs might turn off those gay men looking to converse instead of rave.

Thus, superbars, with their variety of different rooms and their variety of music offerings, hoped to bridge the gap with diverse patrons, allowing something for everybody. Many superbars included TV lounges (this is before TVs were staples at bars), game rooms with pinball machines and pool tables, cabaret lounges, and restaurant spaces. What else made a superbar super? The sheer number of patrons. Some superbars could pack in a few hundred folks into their megacomplexes; others could allow in over 1,500 queer people, an occupancy level the average gay bar just couldn’t handle.

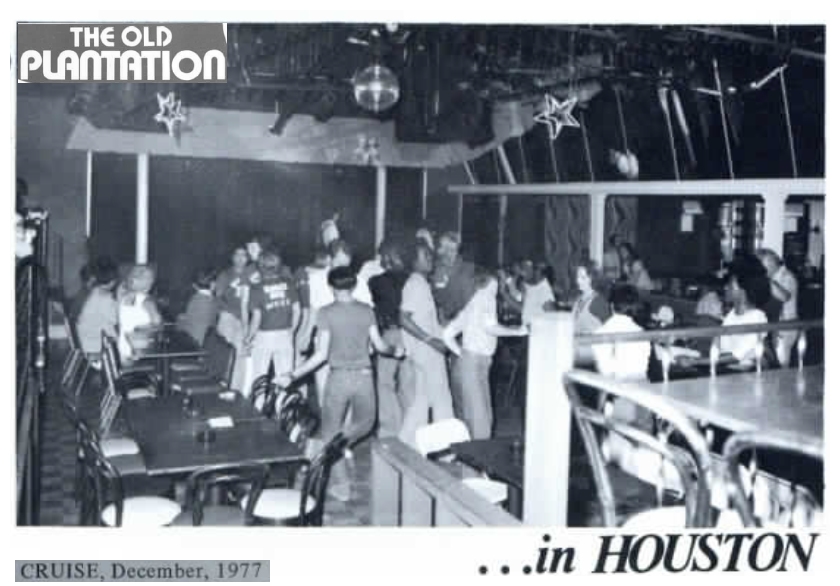

Figure 1. One of the dancefloors of Houston’s The Old Plantation, listed in the 1978 guide as a popular super bar with entertainment, young crowds, dancing, shows, and a pool table. Photo compliment of our friends at HoustonLGBTHistory.org.

The spelling for superbars is all over the place in the historical record, but the Damron guides seemed to have preferred the compound word separated (as in “super bar.”) This is important to take note of because if you’re interested in searching for super bars in our data, you’re going to get different results searching “superbar” vs. “super bar.” Our current search bar also does not read quotation marks as an aid in isolating search results (I know, bummer). This means that searching “super bar” (complete with quotation marks) is not going to isolate just those words next to each other. Instead, the search will look for any mention in the data of QUOTATION MARK super bar QUOATION MARK. So, if you’re interested in finding when Damron identifies super bars in the data, it’s best to search the word “super” or “super bar” (both without quotation marks). You’ll note that this isn’t a perfect method; bars in Superior, Wisconsin show up in the list because the entry includes the word “bar” and “super” (in the title of the city). You’ll also see that Damron occasionally uses the term “super complex” instead of “super bar.”

Important note: This search bar limitation is only temporary; when our team releases our data from 1981-1985, our new search bar will allow for more dynamic inquiries, capable of reading quotation marks, for example. It’s possible you are reading this in the future, in which case: hello, future reader! Do you like the new data??

You’ll note browsing through the super bars listed in the Damron data from 1975-1980 that many of them note the characteristics common to super bars. Badlands Territory in Cincinnati had “many rooms & bars . . . something for everybody.” The Hunt in Indianapolis had three floors and even named the different sections of the club; the upstairs was the “Chase” while the ground floor was the “Lodge.”

Figure 2. T-shirt from “The Hunt,” a venue listed in the 1978 Damron guide as a super bar in Indianapolis. Photo compliment of Wearing Gay History.

It should be noted that while because super bars tried to accommodate patrons with diverse tastes, they were not always nightlife utopias. Several super bars in a variety of American cities were criticized for their exclusionary policies. This included attempts to keep Black, Latino, and women patrons from entering or charging these folks more for drinks or an entrance cover. Interestingly, the Damron guides make no mention of exclusionary policies at Washington’s Grand Central, a bar that according to the 1978 guide included many African American and women patrons. The Grand Central itself is not listed as a super bar either. However, other queer publications saw it as such, and called out the D.C. super bar on what they saw as racism and sexism, or in the words of a national feminist publication, “superbar supershit.” The magazine Off Our Backs told readers to not ignore blatant or subtle discrimination at gay clubs, as “it plays into the hands of racist, sexist bar owners and will ultimately result in all the best dance bars becoming the private preserves of white males.”

Journalists like Terry McWaters writing in the gay publication Queens Quarterly in 1976 reasoned that gay super bars began on the West Coast and spread across the US by the late 1970s, but that claim isn’t represented in our data. That doesn’t mean McWaters is wrong; it just means it’s not a trend we can confirm using the Damron guides. Still, it’s fascinating to read McWaters explain how gay entrepreneurs were “buying up old warehouses, old auditoriums, shuttered movie houses . . . knocking out interior walls here, tearing down there,” all to build spaces “large enough to accommodate the entire gay population of a particular city.” In the end, super bars are a sign that in the post Stonewall era, gay visibility was on the way up, with massive clubs marking gay territory in cities from coast to coast. No longer were gays forced to enter bars in dark alleyways or from the side streets on the outskirts of town; they could now enter massive gay clubs from Main Street, too.

Originally Published: August 3, 2022 | Last modified: August 3, 2022