Does Alabama have an LGBTQ history?

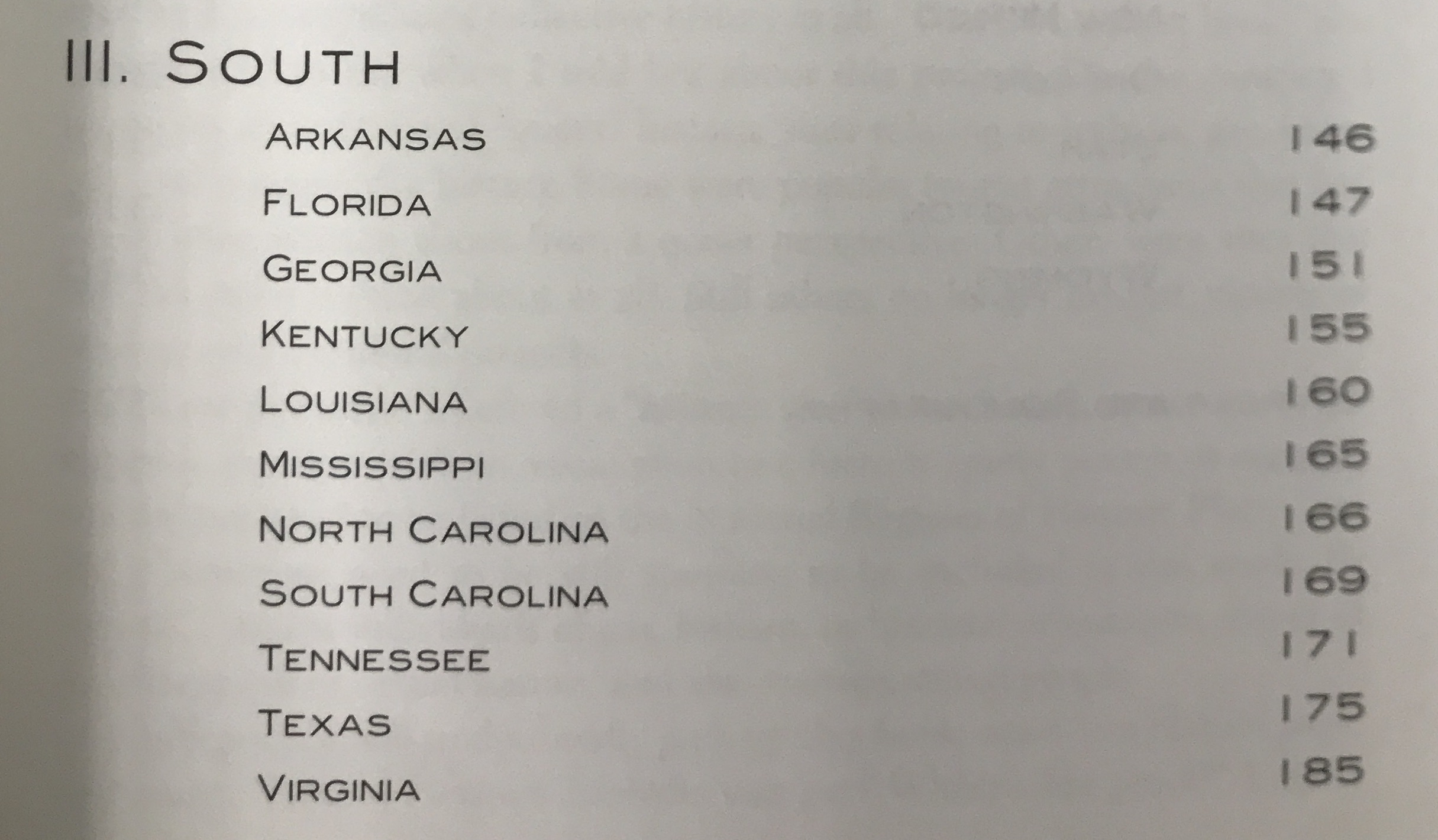

Figure 1. From Martinac’s The Queerest Places. Despite her excellent coverage of the American South, no Alabama sites are listed.

Does Alabama have an LGBTQ history? In her 1997 travel guide The Queerest Places: A Guide to Gay and Lesbian Historic Sites, Paula Martinac provides readers wonderful descriptions of historical places of interest related to queer history. She divides her summaries by states from five regions: New England, the Mid-Atlantic, the Midwest, the West, and the South. Yet, while Martinac lists eleven states in her Southern chapters, no entries from Alabama are included (one of just five states without any listings).

Despite this, there does exist a queer history of Alabama, and a rich one at that. Historians have long focused their work on the epicenters of gay American culture in the last century, principally in the gayborhoods of San Francisco and New York. However, queer life existed outside the American coasts, even in places commonly caricatured as inhospitable for LGBTQ life, like the American South. To try to more closely understand these histories of the queer American South, our team is currently underway on a digital mapping project analyzing ignored queer geography. In February 2020, we plan to launch a map documenting sites of gay life in the U.S. South from 1965-1980

The project utilizes the Damron Guides, an early but longstanding travel guide aimed at gay men since the early 1960s. An LGBT equivalent to the African American “green books,” the Damron Guides contained lists of bars, bathhouses, cinemas, businesses, churches, hotels, and cruising sites in every U.S. state, where gay men could find friends, companions, and sexual encounters. Bob Damron, a resident of San Francisco, began publishing his address books in the early 1960s, identifying gay bars he had personally visited from all around the country. The once pocket-sized books expanded over the years to include tens of thousands of entries from all fifty states and numerous countries around the globe.

Figure 2. This map shows the number of locations listed in the Damron Guides for each year from 1965 to 1980. Use the slider to change the year. Click here for a more expansive map exploring Alabama’s LGBTQ past since 1965.

For this vignette, we have isolated just the Alabama listings in the Damron Address books from 1965-1980, a sort of preview before the official launch of an additional eleven southern states in February 2020. Via this larger map, you can explore the growth of gay sites in Alabama, from just eight (8) listings in 1965, to fifty-seven (57) listings in 1980, an over 600% increase in just fifteen years.

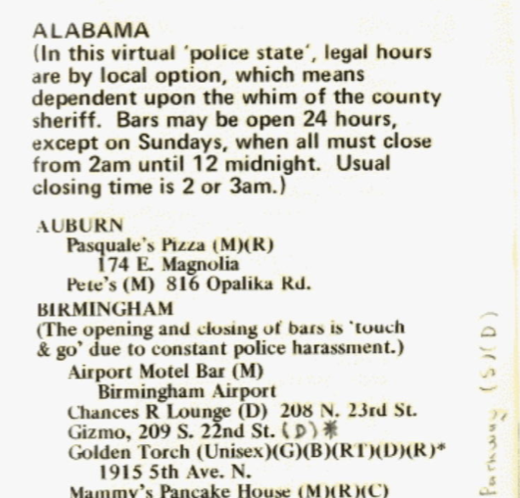

It’s important to remember that the Damron Guides, while offering extensive listings of possible queer spots, aren’t without bias; they sometimes show a coastal perspective to areas thought of as wholly unsafe for queer people, like the U.S. South. For example, in its opening description of Alabama in several 1970s guidebooks, Damron refers to Alabama as a “virtual police state.” While certainly attitudes toward queer people and communities certainly varied across state lines, Damron’s framing of Alabama as a backward place reflects a negative coastal perspective on Southern culture.

Figure 3. From Damron’s Address Book, 1974.

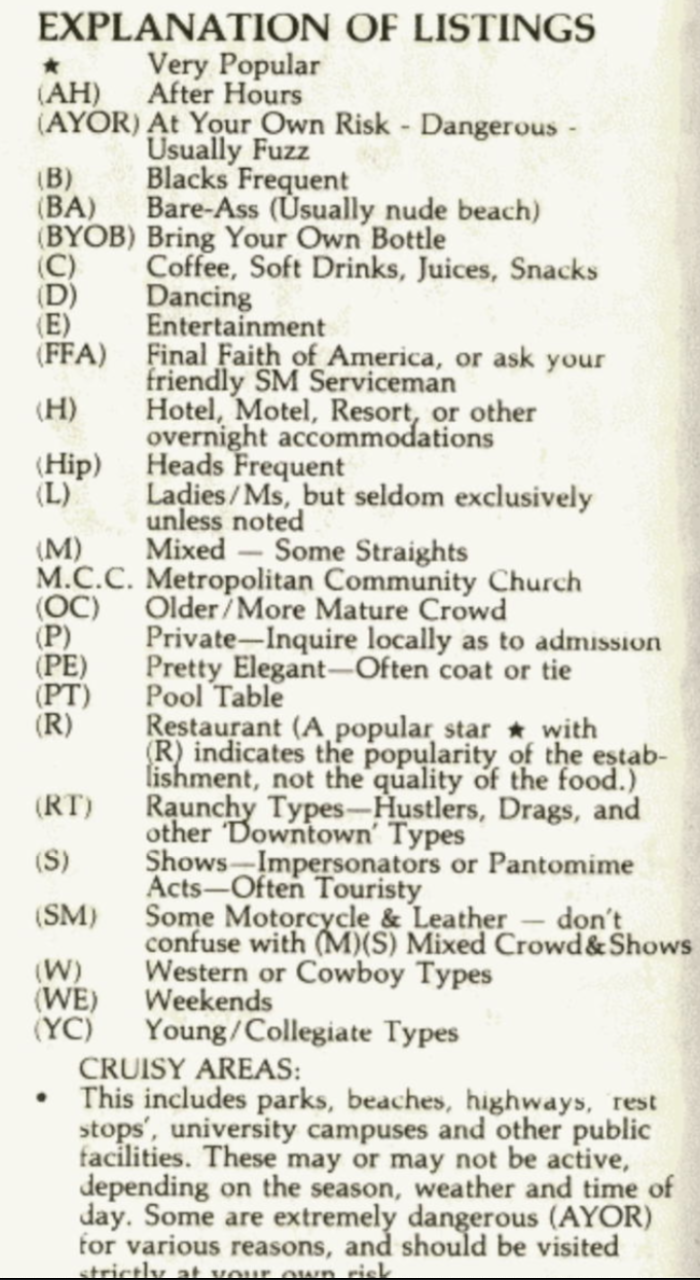

Beyond simply the incredibly increase of listings in Alabama gay sites, readers are encouraged to explore the different categorizations used to differentiate sites in the Damron Guides. Damron used a lettered categorization system, labeling establishments that the writers of the guides felt pertained to certain listings. For example, For example, the 1965 Jewel Box bar at the Dinkler-Tutwiler Hotel is listed as “M” for “mixed crowds” (suggesting a large number of straight people in attendance) and “PE” for “pretty elegant- jacket & tie may be required,” noting that while gay men could find perhaps a friendly atmosphere at the location, it was not without the scrutiny of straight eyes and a formal dress code.

Figure 4. Dinkler-Tutwiler Hotel, listed in Damron’s Address Book, 1965. Photo compliments of the Birmingham Public Archives.

Readers might be surprised to see other famous spots in Alabama history listed as places safe for gay men. The Governor’s House Motel’s Filibuster Lounge bar is listed in 1970 as a spot with “Mixed crowds” but one that gay men could find possible interaction with people like them. The now-destroyed hotel held the election night parties of both Alabama governors George Wallace and Fob James and celebrities like Whoopi Goldberg are among the hotel’s most famous guests. Despite the hotel’s already rich history, Mapping the Gay Guides invites users to understand the often hidden histories of queer people that lay within the state.

Figure 5. Montgomery’s Governor’s House Motel hosted numerous celebrities and Alabama political events throughout its history. It’s inclusion in the Damron guides suggest it has a LGBTQ history as well. Photo compliment of the Alabama Archives

Another example of Damron classifications is the noting of popular “cruisy areas” (places where men could search for romantic or sexual partners). Cruising areas have been staples of gay male geography for decades, perhaps centuries. Unlike other listings in the Damron Address Books, they are largely noncommercial spaces like parks, beaches, city blocks, libraries, etc. where gay men could openly look for companionship. Cruising often proved dangerous, however, and those who partook in the practice faced great risk of being exposed by other citizens or even the police.

In 1980 Alabama, cruising areas centered on the northern half of the state, particularly in Birmingham and Huntsville. In Anniston, Alabama, popular cruising areas included the Greyhound Bus Depot and the blocks around Noble St. In Mobile, a popular spot for gay men to meet, especially in the summer months, was Dauphin Island (incorrectly listed as “Dolphin Island” in its first appearance in the guides in 1973). Far from the gay beach havens on the East Coast like Fire Island or Rehoboth, Alabaman gay men could find perhaps less glamorous but important sites of community near their own hometowns.

One of the most fascinating characteristics collected by the Damron Address books pertain to race. The guides use the letter “B” to designate sites where “blacks frequent.” In the fifteen years currently displayed on the Mapping the Gay Guides, a total of nine (9) unique locations are listed under the “B” symbol. All nine of these locations are either in Birmingham or Mobile. At first glance this may seem odd; neither of these cities lay inside Alabama’s “Black Belt,” where a historical demographic concentration of African Americans have resided since the before the Civil War. However, both Mobile and Birmingham are industrial urban centers with large African American populations. Their sheer size allowed for queer friendly businesses to have a large enough patronage to survive. By analyzing this data via the Mapping the Gay Guides interface, we can see how African American gay men built sites of relative safety and acceptance in an often stereotyped-conservative South.

Figure 6. Explanation of Listings, from Damron’s Address Book, 1980.

While these classifications help us understand the nuances of queer spaces, they sometimes inadvertently promote stereotypes of specific classes of people. For example, a majority of Alabama’s spots listed as “B” for “blacks frequent” also share the label “RT” for “Raunchy types—Hustlers, Drags, or other ‘Downtown’ types.” Hustlers refers to male sex workers, “drags” likely denoting not simply female impersonators but a derogatory term for an unwanted transvestite, and the “Downtown types” likely stereotypes residents of American inner cities. Damron’s marking of relationship between of black spaces with “raunchy” spots likely conflated the residents of inner cities (that is, African American and working-class people) with ideas of vice, crime, and disease. The Mapping the Gay Guides team is excited to explore whether this correlation of black spaces with the “RT” classification is similar once we launch the rest of the US South listings in February 2020.

We invite you to explore the current full map of Alabama’s Damron Address book listing. What changes do you see over the fifteen-year period? Do any of the listings surprise you? What changes do you anticipate once more modern listings are added? Was Alabama really a “virtual police state” toward gay and lesbian people?

We invite you to stay tuned for the launch of the full 1965-1980 US South map set to launch in February 2020. Then, you’ll be able to compare Alabama’s map in relation to eleven other southern states, including Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, and Virginia.

We hope this map helps inspire you to rethink Alabama’s rich LGBTQ history. While town in Alabama like Decatur, Phenix City, and Opelika are quite different from the bustling gayborhoods of the Castro in San Francisco or New York’s Hell’s Kitchen, we hope to show how queer people from all parts of the United States sought to make their hometowns places of survival and safety. Alabama does indeed have a queer past; it’s our job to explore it.

Originally Published: December 1, 2019 | Last modified: December 18, 2019